Gloria Jean (Devorak) Shpak passes

January 2, 2021

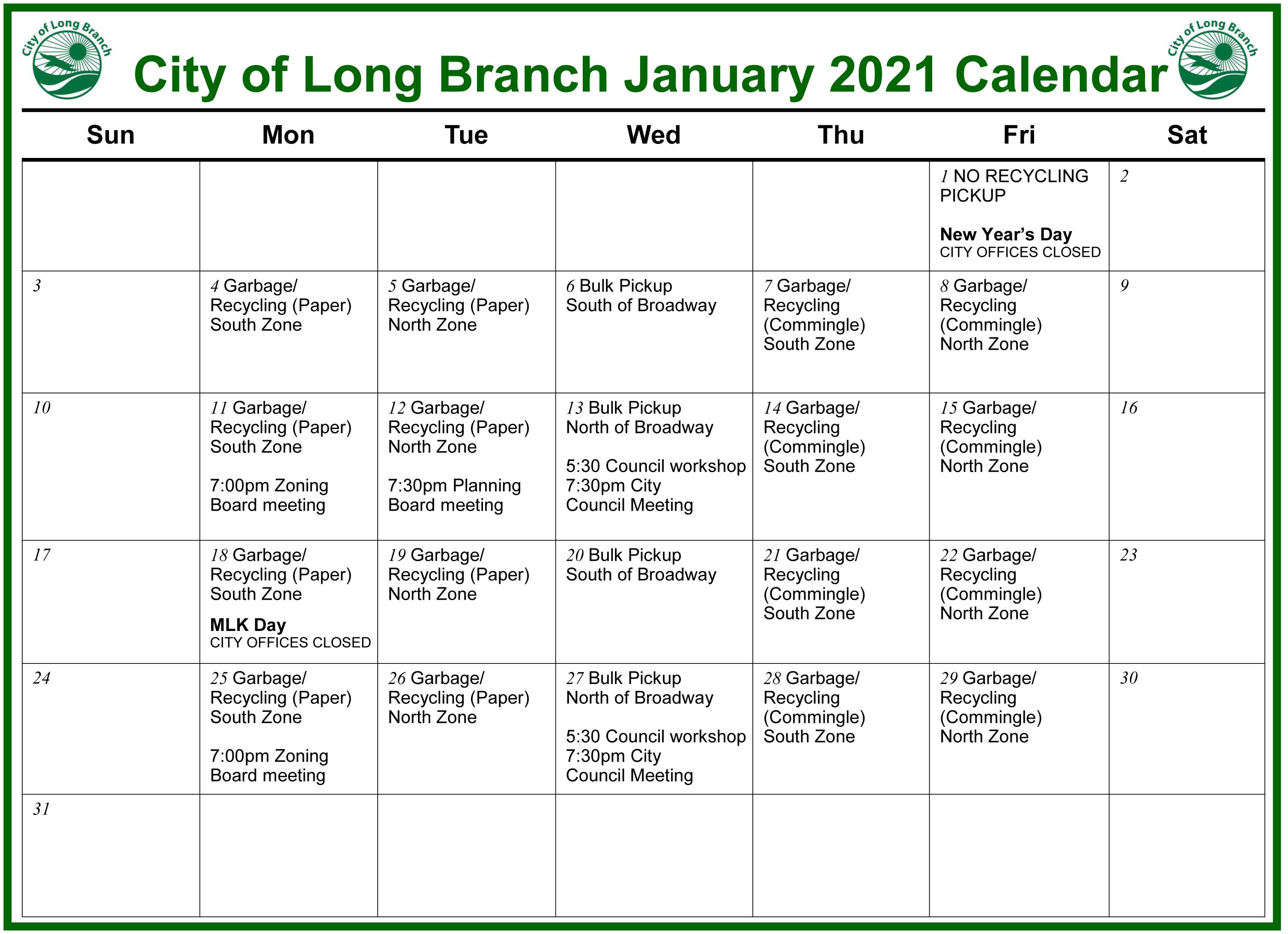

Long Branch garbage pickup calendar

January 2, 2021 The State We’re In by Michele S. Byers, Executive Director, New Jersey Conservation FoundationWinter may seem quiet, almost like nature is taking a break. But is this true?

The State We’re In by Michele S. Byers, Executive Director, New Jersey Conservation FoundationWinter may seem quiet, almost like nature is taking a break. But is this true?

Many animals are hibernating, lots of birds have fled to the south and plants are dormant. But you might be surprised at all of nature’s activity in winter in this state we’re in!

More than a week has passed since the winter solstice – the shortest day of the year – and already the increased daylight is noticeable. Every day for the next six months, we’ll gain a couple of additional minutes of daylight.

Click here for updates in Long Branch

The increasing daylight signals to the natural world that although it’s cold – and will remain so for months – spring is already on its way.

You may have noticed bald eagles carrying twigs and grass. Bald eagles are New Jersey’s early birds, responding quickly to changes in daylight by starting an early mating season. In the chill of winter, eagles are among the first birds – along with great horned owls – to build nests and lay eggs.

Check Ups Are Good For Your Financial Health with Gladstone Financial

Right now, eagles in New Jersey are gathering materials to build or repair nests, many of which are used by the same pair for years. A few females have even started laying eggs! The first bald eagle chicks of 2021 will begin hatching in late February and early March.

How can bald eagles nest so early, when it seems like the cold would be lethal to the eggs and young? The answer is that both males and females are active parents, working cooperatively to keep eggs and babies warm at all times. While one hunts, the other sits on the nest.

The incubation and nesting period for bald eagles is long, so starting early may give them an advantage. By the time chicks are ready to fly and hunt in the spring, food sources like fish, small mammals and waterfowl will be more plentiful.

Great horned owls also mate early for the same reasons. On winter nights when all is still and quiet, you can often hear great horned owls hooting mating calls to each other from the tops of tall trees.

Winter is also mating season for Eastern tiger salamanders, New Jersey’s earliest-breeding reptile. These prehistoric-looking salamanders can grow as long as 14 inches. They’re not easy to spot, though, because they’re nocturnal and spend most of their lives in underground burrows.

On wet nights in winter, Eastern tiger salamanders crawl out of their burrows. Males make their way to ponds and vernal pools – sometimes across snow – where they gather in the water and wait for females.

Female tiger salamanders choose which males get to breed. Once a female has picked her mate, she swims under him and bumps his neck. That’s a signal for him to release sperm into the water. The female absorbs the sperm, later releasing five to eight gelatinous egg masses the size of golf balls.

Once the egg-laying is finished, all parental duties are over. The larvae that hatch in early spring are completely on their own. Eggs laid in vernal pools – that is, ponds that dry up in summer – have the best chance of success, since these bodies of water don’t have fish that would otherwise eat the eggs and larvae.

What other interesting treats does nature offer in winter?

If you’re lucky, you might glimpse an all-white ermine hunting near a stream or lake. Ermine is another name for short-tailed weasel, a native semi-aquatic mammal in New Jersey. Ermine are famous for their snowy fur, but that’s just their winter coloring. In the summer, their appearance changes to brown with white chests and bellies. Like mink and other weasels, ermines are carnivorous.

Most insects disappear in winter, but it’s possible on warm days to spot a beautiful mourning cloak butterfly. In northern areas where it overwinters, including New Jersey, adult mourning cloaks may be seen basking in the sun during almost every month of winter on warm days. These moths have distinctive black wings with small blue dots and a bright golden-yellow edge. You may be able to attract them to your yard by putting out pieces of sweet, overripe fruit, like bananas.

On warm nights, it’s not unusual to see small grayish moths flying around under porch lights and in car headlights. These are male winter moths. These non-native moths emerge from the ground to breed during mild winter weather. Breeding in winter may give these moths an advantage because there are fewer birds around to feast on their eggs, which will hatch in the spring.

Winter is also a great time to observe species that migrate to New Jersey from the north in search of more plentiful food.

For example, seals are regular winter visitors to New Jersey’s shoreline, living in colonies at Sandy Hook Bay and other protected places. Birds that come from the north to spend winters in New Jersey include snowy owls, gannets, loons, snow geese and many waterfowl species. However, these birds don’t breed in New Jersey, so in the spring they’ll return to their nesting grounds in the northern U.S. and Canada.

Even trees have interesting winter tales to tell! For instance, did you ever notice trees with old leaves still clinging to their branches, fluttering in the breeze but not falling off? These are probably beeches and oaks. Beech trees are especially lovely in winter, with pale golden-brown leaves that glow in the sunlight.

Why are beech and oak leaves still hanging on when most trees have long since shed their leaves? Amazingly enough, this may be an adaptation by the trees to protect tender young buds from animals that would munch them. Dried leaves on branches might look unappealing enough to browsing herbivores that they might bypass beeches and oaks in favor of trees with more accessible buds.

Is this due to deer? Probably not, since deer have a short reach and beech and oak leaves can be seen on branches 15 to 20 feet high.

Dr. Emile DeVito, New Jersey Conservation Foundation’s staff biologist and naturalist, points out that only a few thousand years ago, the beech forests of North America were inhabited by giant ground sloths, long since extinct. Giant ground sloths could reach as high as elephants, and were able to nip buds from high branches. Since a few thousand years is the blink of an eye in evolution, trees would not have had much time to respond to the disappearance of giant ground sloths.

Enjoy nature’s unique sights and sounds this winter. Spring may seem far away, but nature’s timeless cycles are reason for hope!

For information about preserving New Jersey’s land and natural resources – including habitats for a diversity of wildlife – visit the New Jersey Conservation Foundation website at www.njconservation.org or contact me at info@njconservation.org.